INTERVIEW: FULL CIRCLE MET MILA V

We spreken Mila V over haar live show in Melkweg: een nieuw hoofdstuk, op een vertrouwde plek.

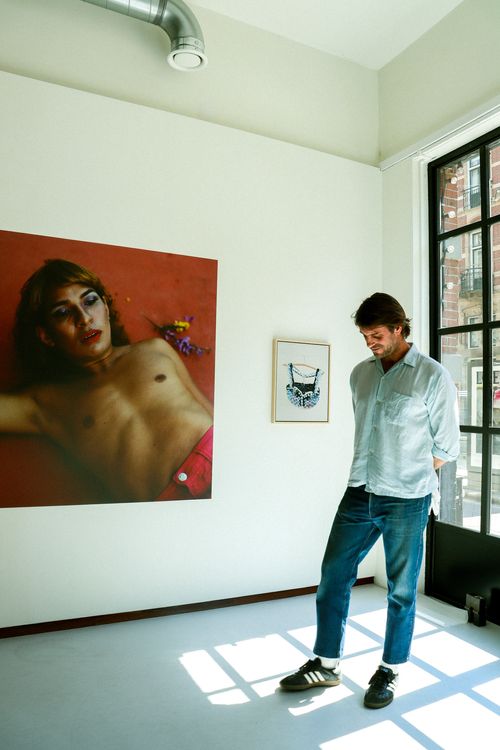

De Amerikaanse fotograaf Daniel Jack Lyons focust in zijn werk op het visualiseren van sociale en politieke rechten van onderbelichte gemeenschappen. Met Like A River, de nieuwe expositie in Melkweg Expo, verkent hij de concepten van identiteit, transformatie en coming-of-age verhalen van gemarginaliseerde gemeenschappen in het hart van het Braziliaanse regenwoud. We gingen met hem zitten voor een gesprek, te midden van de installatie van zijn solotentoonstelling in Melkweg Expo.

This body of work explores how indigenous traditions and modern identities meet. It is set behind the luscious vegetation of the rainforest. Could you maybe start off and tell us a bit more about how you worked at Casa de Rio and ended up in the Amazon?

I met this guy who ran an organization called Casa do Rio in the Brazilian Amazon. He had told me that the organization received funding to do a project on youth empowerment, and was interested in making it an artist in residence. He had seen some work I did in Ukraine, which was a project similar to this one. It was about young people from Ukraine who had left Crimea shortly after it was invaded.

He liked the complexity of showing positivity through the eyes of youth, but with this socio-political backdrop that is quite complex. And he felt that was really applicable to the Amazon. So he invited me as an artist in residence. He said, I'll host you, I'll send you a plane ticket, you live in my house, just take care of the work and if you find something amazing, continue it. That's exactly what happened.

You mentioned there was no set direction for the residency. How did you end up getting to your subject?

Once I arrived, we set up a meeting with a bunch of different young people and I showed my work from Ukraine. I explained that I work on invitation only and I put my phone number on the board. Shortly after that, everybody started texting me saying, let's hang out! I want to take pictures with you! But it was very important for me to meet people and hang out with them, sometimes several times, before we would take a photo.

One of the reasons it's super important to me to do so, is reminding them that once a photograph exists in the world, anyone can see it. So consider how you want to be seen, where do you want to be photographed? What do you want to be wearing? What time of day does it look like to you? How do you want the world to see you? For some people it was very specific. For other people it was very casual.

And from then on, I worked on the project for three years. The pandemic happened in the middle of it. So there was a lot of time spent just chatting with people on WhatsApp. Thanks to this, some very close, intimate friendships were developed through this project, especially with the queer and trans community. So these were not like drive-by portraits. In fact, all day while we're installing this exhibition, I keep taking pictures and sending them to them!

What was it like to get to know their way of queer culture, and how is it different from how we live it?

For me, I was really focusing more on the sameness. I didn't feel a huge amount of difference. Indigenous culture is often linked to this idea of the third gender, and this very profound respect for multiple sexualities and multiple genders. It's great in concept, but just like the Hedras in India: great on paper, but if you visit them, they're horribly discriminated against and the reality is not this fairytale that you read about.

The Amazon is heavily influenced by the whole evangelical Christian movement. These days, even super indigenous tribes go to evangelical churches. So the influence of homophobia from evangelical religion is pervasive as well among indigenous people. Being queer is really difficult for them.

He said: ‘I'm going to do drag for you. So that you can take my photo and bring my drag persona outside of this tiny town, so I can be seen.’

Which brings us back to the portraits. What was it like to collaborate on the photographs, after having talked to them about it?

Everybody had different perceptions of how they would want to be photographed. For example, Wendell. He heard that I came to town, to a meeting that I'd had with all these people. One day, when I was eating at an outdoor table, he rode his motorcycle up to me, and asked: ‘You're the photographer from the US? You're going to photograph me on Thursday. I'll be there at one o'clock.’ [laughs] That’s when we started getting to know each other.

He shared the story that he was just starting to do drag, which is really radical for this town. It's not like there's drag shows, but he would host events in drag. And it was starting to become almost like a comedy act. He lived with his mother - his father's not around - And she has a family business of selling meat in the market. But she became really sick and she could no longer run the business. So Wendell took over the business. And because he didn't want his mother's business to suffer for him being a drag queen, he stopped doing drag.

He shared this with me when we met. He said: ‘I'm going to do drag for you. So that you can take my photo and bring my drag persona outside of this tiny town, so I can be seen.’ The beautiful thing is that Wendell’s mother is actually quite supportive of him being gay and doing drag, which is rare there. She felt really bad that he was making this sacrifice on her behalf. ‘Whatever you need to do to counteract that, do it,’ she told him. So Wendell opened up a home and became the queer mother in the community. When trans girls come out and they get kicked out of their home, they go to Wendell's house. He helps them find a room somewhere.

In fact, Angel was somebody who got kicked out of her family and lived at Wendell's house for a few weeks. He found her a room in another house where she was welcome. Wendell is the connector. So for obvious reasons, when I met him, I met this whole beautiful community of queer people from this tiny village.

Has this project had an impact on your own perception of queerness?

It actually kind of resonated with me. I had my own experiences of a family who didn't support me when I came out. There's a certain shared trauma when you meet other queer people. They could be from another culture that is totally different from your own, but because you both recognize a certain level of queerness, there's like a standard baseline of experience that maybe is in common. And I think that for a lot of the queer people that I connected with, we had that connection of navigating homophobia and navigating a society that isn't accepting. Making these portraits was the creation of a safe space.

And she explained: ‘We’re just a bunch of small streams joining together to make a river. And you are helping us bring us to the ocean and to be seen by the world.’

You mentioned that there was like this deep, intense longing to be seen from within the queer community, the trans and non-binary community especially. What do you mean by that intense longing? And how did that come to light?

The best example I can give is how the name of the book and the series came about: Like a River. And it was because of Angina, you can see her in one of the portraits. She introduced me to a bunch of her trans sisters. A lot of it was on WhatsApp during the pandemic, and she was constantly saying: ‘Oh, this person wants to meet you and wants to be photographed by you’ and I told her, ‘Wow, I feel so honored that so many people want to collaborate and want to make this project work!’ To which she replied: ‘Well yeah, it’s super important to us because you are a possibility for us to be seen.’ She told me: ‘I was born in the same town as Tiago de Melo, a famous Brazilian poet. He wrote my favorite poem: Like A River.’ She recited it for me, and there’s this part in the poem which mentions how a river is just a sum of small streams that eventually meet at the ocean.

And she explained: ‘We’re just a bunch of small streams joining together to make a river. And you are helping us bring us to the ocean and to be seen by the world.’ That’s how the title came about.

It sounds like the project felt like a safe space to the community. Did you face any challenges while being there and working on them?

You know what? Not really. And I think that one of the reasons I didn't is because people really had my back. So I never felt threatened. And because I speak fluent Portuguese, nobody was able to get anything by me. If some person was being homophobic, I would catch it.

The biggest challenge for the project, which ended up becoming a blessing, was the pandemic. When starting the project we were having this really great momentum. And then I was scheduled to go back, that’s right when everything happened. That seemed like it would be a big setback. Maybe I would just have to either work with what I have or, you know, just cancel it.

But there is the fine silver lining was that we were already connected on WhatsApp, so we all just kept in touch. And it was one of those rare experiences where everybody in the world was experiencing the same thing and we had a lot of time on our hands. So almost every day I was checking into people. How are you doing? What's it like in Brazil right now? Are you getting a vaccine? As soon as I got the vaccine, I was there. So when arrived and then there were all these new people that I hadn't met yet! But I knew them super well because we'd been in touch for almost a year every day. So it was quite beautiful in that way.

As you’ve mentioned earlier, you’ve been updating them on the installment of Like A River here in Melkweg Expo. How is everyone in responding to seeing the exhibition come to life in this space?

Wendell has sent me these voice messages that are like: 'Oh my God, my heart! I'm enchanted' in Portuguese, which doesn't really translate to English. He also sent a text: ‘Wow, congratulations! Thank you for allowing me to be part of this great project. I am so grateful that you permitted me to collaborate in this project with you.’ I replied to him: 'Are you kidding? I am so grateful to you for permitting me to collaborate with you!' Everyone is thrilled.

You worked on this project for three years. From staying in Carreiro, to publishing the book and now your first big solo exhibition with the work. What has that been like for you, and what is it like to see it come together in Melkweg Expo?

Oh, it's so exciting. Every step of this project has had this spirit of collaboration. I was really appreciative to make the book with Loose Joints, my publisher, because I always wanted to make the book with people who are artists in their own right at making books. I was bringing the photos and they're bringing their expertise in making books.

And then working on this show with Claire [Expo Marketeer], it is the same thing. We’ve been totally on the same page. We both came to our meetings with 'I've got this idea. I'm thinking fabrics.' She was like: 'Ah, let me show you the fabrics that I'm thinking of!' She already had references! So it was just like that spirit of collaboration carried through from the beginning of the project all the way to this exhibition.

What would you like the visitor of this exhibition to go home with? What kind of impact would you like to make?

What I would be grateful for is if people related to this on a really deeply personal level, because for me, the connections made are so personal and intimate. These are my friends.

And I think that, so often with projects that relate to the Amazon, there's this idea that the Amazon is a forest. It's a biome. It's the lungs of the world. Or if we think about the people in the Amazon, we think about these tribes that are super remote and really rural and untouched by Western society. And sure, that exists. But there's this other side where there's queer people just like me and you. There's rappers and skaters and teenagers hanging out with each other, creating a community, creating chosen families, navigating the same societal challenges that we navigate sometimes here in the West. So I think for me, I would love for people to, instead of thinking of the Amazon as a big forest, they can look at it with much more human context.

Exhibition images: Daniel Jack Lyons

Interview photos: Valérie Broek